Chapter 5

Labeling Your Ailments with an Accurate Diagnosis

In This Chapter

- Understanding what to expect

- Deciding when you need to see your doctor

- Teaming up with your doctors to find the problem food(s)

- Picking a food allergist who’s best qualified to treat you

- Assessing the usefulness of allergy tests and other diagnostic tools

When you can’t eat without breaking out in hives, having your ears puff up like muffins, or getting the collywobbles, obtaining an accurate diagnosis can calm your anxieties. I’m not saying that being diagnosed with a food allergy is cause to celebrate, but diagnosis is the first step to relief.

In this chapter, you take the first step on your diagnostic journey by completing a self-screening test. Although this test isn’t intended to be a self-diagnosis, it can assist you in deciding whether you need to visit your family physician or an allergist for a more thorough workup. The self-screening test also guides you through the process of logging information that can be very useful in your diagnosis.

With your self-screening test in hand, you and your doctor can then embark on your search for the offending food(s). To assist you, I provide plenty of guidance and tips on how to team up with your family physician (or pediatrician) and allergist to more effectively determine if you do, in fact, have a food allergy, and (if you do) expedite the process of identifying the food(s) that ail you without overly restricting your diet. I also show you the sorts of allergy tests and other diagnostic routines you can expect, so you won’t be taken off guard by any of your doctor’s recommendations.

Tip: In this chapter, I refer to many of the common symptoms of food allergy. For a more complete discussion of symptoms and possible causes, check out Chapter 2.

Taking a Flyover View of the Diagnostic Journey

The path from the point at which you feel ill to the point at which you receive a diagnosis and treatment plan can be a long and winding road. To assist you in navigating that path, check out this eye-in-the-sky overview of the diagnostic process:

- Your general practitioner (GP) performs a physical exam and jots down your medical history. The history is critical in ruling out other possibilities, identifying the likely problem foods, determining which tests are most appropriate, and guiding the interpretation of test results. See “Taking a Trip to Your General Practitioner.”

- Your GP refers you to an allergist. An allergist, particularly one with experience in diagnosing and treating food allergies, can perform additional tests and is usually more qualified to interpret the test results. See “Seeking an Allergist’s Advice.”

- Your allergist performs a complete food allergy workup. Like your GP, your allergist is likely to perform a physical exam and take additional notes about your medical history. Your allergist is likely to perform several tests to identify the problem food(s) and rule out suspects that are not involved:

- Skin tests: Skin testing is used only in the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergies—allergies in which your immune system produces IgE antibodies to a specific food. An allergy specialist (rather than your GP) should perform the tests, because of both the risk of anaphylaxis and the skill required to properly interpret the results. A positive skin test to a particular food indicates only the possibility that you’re allergic to that food. Your allergist may need to perform additional tests to confirm that eating the food causes you to react. In contrast, a negative skin is about 90 percent accurate in determining that you’re not allergic to the tested food. See “Poking around with skin tests,” for details.

- RASTs: Short for short for radioallergosorbent tests, RASTs look for the presence of food-specific IgE in the blood. These tests are widely available and are unaffected by the presence of medications. In at least one study, RASTs have proven very effective in diagnosing several of the major food allergies in children. RAST results show the concentration of IgE in the blood, and we have established RAST levels that can predict with about 95 percent accuracy whether a child is allergic to egg, milk, peanut, tree nut, or fish. A child with a test result exceeding the established value, in combination with a positive skin test, does not require food challenge for definitive diagnosis. See “Hunting for IgE with RASTs,” later in this chapter.

- Food diary: Your allergist may ask you to keep a food diary listing the foods you eat and drink and recording any reactions to those foods. A food diary can be useful in identifying overlooked foods, hidden ingredients, and patterns of reactions. See “Preparing to have your history taken,” later in this chapter.

- Diagnostic elimination diet: Your allergist may order you to stop eating one or more foods to see if symptoms disappear, which would identify the problem foods. The allergist needs to pay careful attention to nutrition whenever removing an essential food from the diet of a growing child. See “Discovering your allergens by avoiding them,” later in this chapter.

- Food challenges: A food challenge consists of eating the problem food under your allergist’s supervision. Results of a food challenge provide the most definitive data for diagnosing a food allergy. Your allergist will select foods for testing based on the history and the results of skin and/or RASTs. Only a qualified allergist who’s familiar with food-allergy reactions and is equipped with the necessary emergency medications should perform a food challenge. See “Daring a food to make you react: Food challenges,” later in this chapter.

- Your GP and allergist may order additional tests if symptoms persist. You may have a non-IgE mediated food allergy, as discussed in “Pursuing the causes of non-IgE mediated allergies,” later in this chapter, or you may have a food intolerance (see “Ruling out food intolerances,” later in this chapter).

Warning: The journey from problem to solution often requires time, patience, and persistence. Don’t try to take a shortcut by reaching for untested, unproven alternative tests and treatments. See “Avoiding the untested and unproven,” later in this chapter, for details.

Self-Screening for Food Allergies

Funny thing about people in general (specifically men)—they don’t like going to the doctor. They often prefer to tough it out, hope it goes away, or convince themselves that the doctor “can’t do anything” rather than seek immediate medical care. With food allergies, however, avoiding the doctor can be dangerous, because the longer you tough it out without an accurate diagnosis, the more likely your reactions are going to increase both in frequency and severity.

Remember: Allergic reactions begin and intensify with increased exposure to allergenic foods. Early diagnosis and an effective treatment plan can not only make you feel better now but also prevent you from feeling much worse down the road.

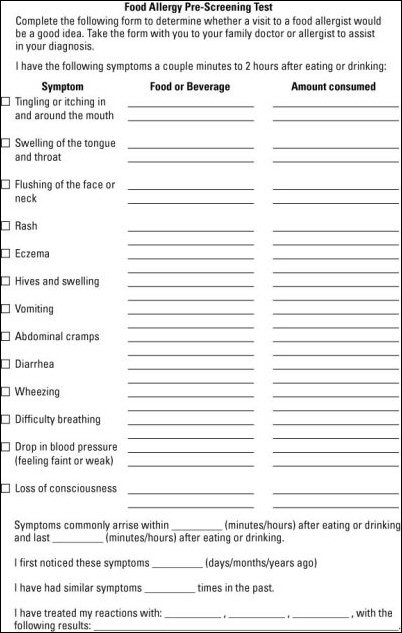

If you or a loved one is experiencing mysterious symptoms, particularly a couple minutes to a couple hours after consuming food or beverages, you may have a food allergy. Complete the self-screening test shown below. This self-screening test serves three very important purposes:

- Assists you in deciding whether you need to see your doctor or allergist. (If you have any doubt after completing the test, see your doctor anyway.)

- Provides you with a log of symptoms and other concrete details that you can present to your doctor or allergist, which may be key to an accurate and early diagnosis.

- Hones your observation and record-keeping skills, which are two of the most valuable skills for any person who has a food allergy or is caring for someone with a food allergy.

Warning: This self-screening test is not a self-diagnosis. Identifying specific allergens is tricky, even for a well-trained and experienced allergist, and you may be allergic to multiple foods. In addition, other conditions can produce symptoms similar to those of allergic reactions. Use the self-screening test only as a tool to facilitate a professional medical diagnosis and treatment.

Taking a Trip to Your General Practitioner

When you first suspect that you have any health problem, the first doctor you typically go to see is a general practitioner (GP for short)—your family physician, pediatrician, or internist. In the following sections, I reveal how a GP can and cannot help you with food allergies, when and how to request a referral to a food allergist, and how to avoid quacks who promise everything, deliver little or nothing, and often discourage you from seeking effective treatment.

Why see your GP?

In the case of food allergy, seeing your GP first is a good idea for the several reasons:

- Your GP possesses a breadth of knowledge and training that’s often useful in identifying not only food allergies, but also other conditions that may produce similar symptoms.

- The GP can coordinate the oversight and management of all of your healthcare needs, not only your concerns about allergies.

- Your GP often has access to your entire health history and may be able to spot patterns in your family history that make certain conditions more likely than others.

- Your health insurance may require you to see your “primary care physician” (your GP) before approving your visit to a specialist.

- Your GP can refer you to a qualified food allergist, often one that’s in the same insurance network and perhaps in the same office complex.

Knowing what to expect from your your GP

Some GPs know quite a bit about food allergies. Pediatricians may even know a bit more, because food allergy is most common in young children. So what’s your GP supposed to do? In the following sections, I describe the standard care you can expect from your GP. If you’re not receiving a standard level of care, express your expectations to your GP. If you’re still not satisfied, you may need to look for another doctor.

Remember: Most patients love their GP’s and are satisfied with the general care they provide, but the number one complaint I hear from patients is this: “How could my doctor (pediatricians included) have been so ignorant about food allergy?” Many patients report symptoms of food allergy to their GP’s for years before their GP’s take the reports seriously. (GP’s generally take reports of severe reactions seriously and refer patients to an allergist immediately, but they frequently miss the signs of more subtle reactions.)

Recording your history and equipping yourself for potential emergencies

The least your GP should do is ask you a lot of questions, record a detailed history of symptoms and what makes them better or worse, and determine the likelihood that you’re at risk for severe or life-threatening reactions—that is, whether you may have an IgE-mediated allergy, as described in Chapter 2. If your doctor suspects that you have an IgE-mediated allergy, she will likely take the following steps:

- Identify suspected food(s) to avoid until you can get in to see the allergist.

- Refer you to an allergist.

- Hand you a prescription for autoinjectors, such as an EpiPen or Twinject, as a precaution in the event that you experience a future anaphylactic reaction. (See Chapter 10 for details on getting your emergency kit together.)

Warning: To err on the side of safety, assume that the next reaction is going to be more severe than the previous reaction and equip yourself to deal with it. Just because a child developed hives only on her face during her first reaction to milk or egg, you can’t assume that the next reaction is going to be of a comparable intensity.

Initiating allergy testing

Your GP may or may not decide to initiate allergy testing. Very few GP’s have the training or materials to perform skin tests, but any doctor can perform blood testing for allergies (see “Hunting for IgE with RASTs,” later in this Chapter). RAST (radioallergosorbent test) results can be very helpful in proving that the suspect food really triggered your reaction. However, searching for culprit foods with extensive panels of tests—that is, by ordering tests for hundreds of foods—is usually a huge waste of time and money and risks returning a number of false positive tests which only complicates the diagnosis.

Tracking down other potential causes

If your doctor doesn’t suspect an IgE-mediated allergy, then she should attempt to determine whether the reaction represented some other type of food allergy or a nonallergic food reaction (a food intolerance, as explained in “Ruling out food intolerances,” later in this chapter). The diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated food allergy often requires the assistance of a gastroenterologist as well as an allergist. In some cases, the history may be insufficient for discerning the cause of a particular reaction. This is most often the case with patients who have isolated gastrointestinal symptoms. In such instances, your GP should arrange for further evaluation and proceed as if the reaction were IgE-mediated, including equipping you with epinephrine if suspicion is sufficiently high.

Advising you until further notice

Based on your history and any test results, your GP should tell you which foods to avoid until further evaluation. Your doctor should carefully interpret the RASTs, since you can often test positive for safe foods, and you don’t want to be saddled with an overly restrictive diet. In some cases, a GP orders RASTs but is not fully competent in interpreting the results. Have your RAST results forwarded to the allergist you decide to see.

Remember: When you’re on an extremely restrictive diet, meeting your nutritional needs can be tough, especially for infants and children. If your doctor prescribes extreme restrictions, he’s likely to refer you to a nutritionist, as well. If he doesn’t refer you, request a referral, as explained in the section, “Navigating the referral process,” below.

Navigating the referral process

You visited your GP, she took a detailed history, told you that you probably were suffering from a food allergy, and referred you to an allergist. Good for you. You’re now on your way to a more thorough workup and can skip ahead to the section, “Teaming up with your allergist for optimum results.” If, on the other hand, your GP offers no reasonable alternative diagnosis or effective treatment and is reluctant to refer you to an allergist, you may have to crank your efforts up a notch:

- Ask your GP if she thinks the symptoms could be symptoms of food allergy. Sometimes, this is enough to lead a GP on the right path.

- State the reasons why you suspect food allergy. Use your powers of persuasion to convince your GP that food allergy is a possibility and that a specialist can help confirm your suspicions or rule them out.

- Request a referral. If your insurance plan requires a written referral from your GP in order to cover your visit to a specialist, your goal is to walk out of your doctor’s office with a referral. (See the following sidebar, “Referrals past and present,” for details.) Don’t be shy, and don’t take no for an answer.

- Call your insurance company. Look on the back of your insurance card for a toll-free number. Following are some guidelines and talking points:

- Always write down the name of the insurance company’s representative you talked with, the date and time, and specifically what the person told you.

- Ask if your policy requires referrals (some don’t). You may be able to see an allergist without your GP’s referral. If your plan doesn’t require a referral, the cost of seeing an allergist is typically the same as it would be if you had a referral; you’d have to make a co-pay out of pocket.

- Ask what happens if you see an allergist without a referral or one who’s not in the insurance company’s network. Your policy may not cover out-of-network doctors or cover a lower percentage of the cost than if you were to see an in-network specialist with a referral from your GP.

- See a food allergist without your doctor’s referral or your insurance company’s approval. This is usually the most costly option, because your insurance company may not pay any of the cost.

Tip: If you have to pay out of pocket for tests and treatments, mention this to your doctor. Doctors are human beings who are well aware of the high-cost of medical care. They may offer you a discount or be willing to set up a reasonable payment plan and will often be willing to charge you what they would normally get back from the insurance company (an average of a 36 percent discount).

Referrals past and present

In the not-so-good-old days, health insurance companies often set strict limitations on referrals. Sometimes they penalized GPs for sending too many patients to specialists or offered rewards to GPs who issued fewer referrals. (In the real old days, prior to 1990, GP’s didn’t need to worry about this nonsense.) Fortunately, most insurance companies have ended their Draconian policies and now give their doctors carte blanche to make as many referrals as necessary. Some companies don’t even require referrals, so patients are free to see whichever doctor they deem most helpful.

If your GP seems reluctant to refer you to an allergist, don’t be quick to blame your insurance company. In most cases, your GP’s reluctance is based more on the fact that your GP really does not believe that you have a food allergy. If your doctor is unwilling to assist you in obtaining a referral to an allergist, become more proactive. Contact an allergist yourself, and see if your allergist can obtain the insurance approval you need.

Remember: GPs often have the mistaken notion that allergists can’t perform allergy tests on children until they’re two or three years old. This is clearly wrong. The consensus of food allergists is that the GP should make the referral as soon as possible after concerns of food allergy arise, even in a two- or three-month-old. The medical community has plenty of evidence that early diagnosis and treatment greatly benefit children and their families.

Avoiding quackologists

Alternative therapies for food allergies abound. Chiropractors, nutritionists, acupuncturists, and a variety of other alternative practitioners claim the ability to diagnose and treat food allergies. Some of these healthcare providers may even be quite knowledgeable about food allergies and beneficial in your care. Other practitioners who are more on the fringe or way out there, tout their snake-oils, magic potions, crystals, and other treatments that range from entertaining diversions to dangerous delusions.

Warning: Don’t fall for pumped-up promises of miracle cures. Seek well-trained, qualified medical practitioners to diagnose and manage your food allergies. If you do decide to pursue alternative routes—a chiropractor with an interest in food allergy, for example—I always advise that you see a traditional allergist as well. For details about the most common quack tests and treatments, skip to Chapter 8.

Seeking an Allergist’s Advice

Your doctor decided to call in an allergist, or you decided on your own to pursue this option. Now you’re in the market for a top-notch allergist. But what exactly qualifies an allergist as top-notch? Here are the qualities to look for in an allergist:

- Training and experience with diagnosing and treating food allergies: This may seem like a “well, yeah, duh” recommendation, but many allergists are better trained to deal with general allergies, such as allergies to pollen or pets. Not all allergists are up to speed on food allergies, particularly in complicated cases.

- Well-honed interpersonal skills: Some allergists are extremely bright and well-informed but have the interpersonal skills of a mannequin or a personality that clashes with yours. They may take your concerns lightly, rush you through your visit without answering your questions, or have some other issues that make for a less than ideal fit.

In the following sections, I show you how to track down an ideal (or at least close-to-ideal) allergist and team up with your allergist to obtain the most accurate diagnosis and most effective treatment plan.

Tracking down a qualified food allergist

Tracking down a local allergist who’s best qualified to diagnose and treat food allergies is a four-step process:

- Gather recommendations from your doctor, friends, and family.

- Ensure that your insurance policy covers the allergists on your list.

- Verify the allergist’s credentials.

- Check the allergist’s availability and make an appointment.

The following sections explain each step in greater detail.

Gathering recommendations

Your first recommendation typically comes from your GP. Your GP should be familiar with the allergists in your area, hopefully knows which allergists have expertise in food allergy, and may even know who would be the best fit from a style and personality standpoint.

If your GP doesn’t recommend a suitable allergist or you want additional input, ask everyone you know and trust, especially friends and family members who’ve already seen an allergist. Ask other doctors if you happen to know any. These people are often even more capable than your GP in helping you find the perfect doctor.

Tip: If you’re in a food-allergy support group, which isn’t likely at this point because you’re just getting started, recommendations from fellow members are pure gold. People often change allergists later based on recommendations from other members of the group.

Checking insurance coverage

Now that you have a long list of candidates, you can start paring down your list by crossing off any allergists not covered on your insurance policy. To see if a particular doctor participates in your insurance network, do one of the following:

- Call the doctor’s office, provide them with your insurance company’s name and the network you’re in (almost always printed on the health insurance card), and ask if the doctor is in your network. Most allergists participate with all of the larger insurance companies, so your selection shouldn’t be overly limited.

- Check the approved provider list supplied by your insurance company. Many insurance companies offer members a book of approved healthcare providers, typically grouping providers by location and specialty. If you don’t have such a book, request one. Your insurance company may also have a Web site where you can look up the names and contact information for allergists and other doctors and specialists in the company’s approved network.

- As a last resort, try calling the company for additional information, especially if you lost or misplaced your approved provider list or it’s a couple years old. A newer list may contain the name of the allergist you want to see.

Verifying the allergists’ credentials

When your GP refers you to an allergist, ask about the allergist’s credentials and bedside manner to learn as much as possible about his training and experience. If your GP is less than forthcoming or you obtained a recommendation from someone who has little solid information, the following organizations can help you gather information and can even provide you with additional names if you’ve come up short after talking to your GP, friends, and family:

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (www.aaaai.org)

- American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (www.acaai.org)

- American Academy of Pediatrics (www.aap.org)

- American Board of Medical Specialties (www.abms.org)

Tip: Other local medical societies may be able to provide additional recommendations.

Getting in to see your allergist

Rank the allergists on your list from first choice to last choice based on qualifications, reputation, and location, and then start calling around to make an appointment. Unfortunately, many allergists have a long waiting list, often several months. If you feel that you can’t wait that long, you may need to go with your second or third choice.

Still having trouble getting in to see the allergist? Here are some tips and tricks from seasoned patients:

- Set up appointments with two or more allergists. When you finally get in to see one allergist, you can cancel the appointment(s) with the other(s). Don’t cancel unless you’re happy with the first allergist you see.

- Ask your GP to call the allergist directly to see if she can fit you in sooner. Your doctors may agree that waiting until the next available appointment could be dangerous.

- Ask to be placed on the allergist’s cancellation list. If a patient with a scheduled appointment calls to cancel, the allergist can give the appointment to you. My co-author, Joe, who works at home (that lucky dog), has had great success using this strategy to get his kids in to see their specialists.

Tip: After you see your allergist for the first time and assuming you’re happy with the allergist, don’t leave the office without setting up at least one appointment in advance. This can trim your wait time in the future. If you don’t need the appointment, cancel it a week or so in advance as a courtesy to other needy patients.

Teaming up with your allergist for optimum results

No matter what kind of healthcare issue you have, you get the best results when you team up with your doctor. To effectively team up with your allergist, here’s what you do:

- Be open and honest. If you smoke or drink alcoholic beverages, for example, let your allergist know. If you have other health conditions, even if you think they’re unrelated, inform your allergist. This is no time to be hiding important details.

- Write down any medications you’re currently taking. Although medications don’t typically trigger allergic reactions, they assist your allergist in painting a more accurate portrait of your condition, and your allergist needs to know of those medications in order to safely prescribe other medications.

- Ask questions, even if they seem dumb to you, and express your concerns. Keep those lines of communication open.

- Listen carefully to what your allergist says and follow her advice.

- Keep in touch between appointments either over the phone or via e-mail, so your allergist is privy to any problems or questions that arise.

- Work with your allergist to develop an emergency back-up plan, in writing, in the event that you experience a severe reaction. (Chapter 10 provides additional information on planning and equipping yourself for emergencies. Check out Chapter 7 for a form you can fill out to get your emergency action plan in writing.)

Getting the Skinny on Allergy Workups

Diagnosing a food allergy is about as challenging as finding an allergist who can see you the next day. Your allergist is likely to take a detailed history, perform a physical examination, and proceed with a battery of diagnostic tests to figure out what’s going on and which foods are the prime suspects.

Remember: The diagnostic process is more complicated if your food allergy is not IgE-mediated, since the most common allergy tests—skin tests and RASTs—both rely on the presence of IgE antibodies. These tests are useless in diagnosing non-IgE mediated food allergies.

In the following sections, I lead you through the diagnostic process step-by-step, so you know what to expect along the way.

Making the most of your medical history

Your medical history is of tremendous value in diagnosing food allergy, so don’t forget to bring the self-screening test you completed in the section “Self-Screening for Food Allergies,” to your first appointment. In addition to what you’ve already recorded, your allergist is likely to ask you a series of probing questions to determine whether true food allergy is likely, and whether the allergy is likely to be IgE mediated.

Preparing to have your history taken

You can prepare for the doctor to review your medical history by jotting down your answers to the following questions:

- What foods do you suspect you are allergic to?

- At what age did the suspected food allergy begin?

- What were your specific symptoms?

- What was the timing of the suspected reaction(s)?

- Did your reaction occur soon after eating the suspect food?

- Does a reaction always occur when you eat that food?

- Had you previously tolerated that food? How often have you eaten it?

- How much did you eat before you had a reaction?

- Did anyone else who ate the same food get sick?

- How was the food prepared? How likely is it that the food had hidden ingredients?

- Were any medications used to treat the reaction? If medications were used, which meds were used and were they effective?

- What were you doing prior to or during the time you had the reaction? Just eating? Exercising? Taking a bath?

- Have similar reactions occurred on prior occasions?

Using your answers to these questions, your allergist formulates your medical history—one of the most important and useful diagnostic tools. Your allergist may also ask you to keep a food diary to find out even more about your diet and symptoms in an attempt to identify any consistent pattern to your reactions.

Investigating your history for clues

Although your history is the most important diagnostic tool, its usefulness varies depending on the results. Typically, the history leads to one of the following two common scenarios:

- Bingo! The history is precise and virtually diagnoses your specific food allergy all on its own. If you break out in hives the first time you eat an egg, for example, it’s pretty obvious that you’re allergic to eggs. In this case, further testing usually confirms the suspicion.

- I dunno. With more subtle symptoms, especially eczema and some of the non-IgE mediated gastrointestinal food allergies, reactions may be quite delayed. You may have had three or four meals and several snacks before you started feeling ill, making any clear link between cause and effect very difficult.

Remember: Several studies show that further testing confirms a history of suspected food allergy only about 30 to 40 percent of the time. Your allergist must interpret your history, including food diaries, with great caution.

Getting physical with a physical exam

You could place a pretty safe bet that by the time you get in to see the allergist, your symptoms will have magically disappeared. Your allergist asks to see the hives, and your skin is perfectly clear. Your tummy which was as bloated as a beach ball two days ago is as flat as an ironing board today. Even your sinuses are clear.

Even so, your allergist is going to perform a physical exam to look for signs of a possible food allergy, such as eczema and other rashes and symptoms of other allergic reactions, such as hay fever. What does hay fever have to do with food allergies? Well, food allergy is more likely to occur in those who have other types of allergy, and this can be an important clue.

Remember: The physical exam, in and of itself, is not always conclusive. Your exam may reveal no abnormalities, even if you have severe reactions to multiple foods. After all, the only good thing about food allergy is that you usually look and feel fine as long as you’re abstaining from the problem foods. One important bit of information a normal exam provides is that it reassures you and your allergist that you’re probably okay with your current diet.

Poking around with skin tests

Once your allergist commences testing, you may begin to wonder if you mistakenly stepped into the acupuncturist’s office. Allergists commonly perform skin-prick tests in which they poke or scratch the skin with an extract of the suspect food and observe any reactions on the surface of the skin. Your allergist may use any of the following three methods:

- The allergist places a tiny drop of food extract on the skin and pricks the skin through the drop with a small needle or plastic probe.

- Using a pricking device soaked in the food extract, the allergist pricks the skin.

- The allergist inserts a small amount of the food extract into the skin using a small needle. This method, called intradermal skin test, is rarely, if ever, indicated for food allergy diagnosis.

A positive skin test results in a mosquito bite-like reaction at the site of the test within minutes, indicating the presence of histamine, which causes the skin to swell. After 10-15 minutes, your allergist takes a reading and compares all tests to a control prick (to test your reaction to salt water, which shouldn’t cause a reaction). A larger reaction—a larger bump on your skin—typically shows an increased likelihood that you’re allergic to the tested food.

Guesstimating the number of pin pricks

How many times can you expect to get poked? If you’re presenting symptoms of a nonfood allergy, such as hay fever or asthma, your allergist performs a fairly standard set of tests consisting of 20 to 40 skin pricks.

With food allergy the number of tests is typically based on patient history, so you can’t expect a set number. An allergist usually performs skin prick tests for only suspect foods. If you’ve had only one reaction to milk, for example, your allergist is likely to test only for milk to confirm suspicions. If the history identifies no particular problem food—you have eczema, for instance, but no specific food reactions—then, your allergist is likely to test for only the five or six most common food allergens, including milk, egg, soy, wheat, and peanut.

Warning: Be cautious of any allergist who recommends dozens of tests for food allergies. A few allergists out there routinely test every patient who walks into their office for 120 different foods, even if they have no reason to suspect a food allergy. Studies show that in children with eczema, if the skin prick tests or RASTs results are negative for the most common food allergens, the children are highly unlikely to be allergic to less common allergens.

Acknowledging the challenges of interpreting skin tests

Interpreting a skin test seems like a snap. Either it’s positive or negative. What’s so tricky about that? Actually, it’s tougher than it sounds.

The easiest result to interpret is when the test is completely negative. When you test negative for a particular food, the likelihood that you have an IgE-mediated reaction to that food is next to nothing. The main exceptions occur in babies in the first six to nine months of life, during which time occasional false negatives occur.

Remember: Skin tests are positive only if you have IgE antibodies to the food being tested. Skin tests do not detect non-IgE mediated allergies.

Interpreting positive food skin test results is more problematic. Positive tests indicate that IgE is present but do not, without confirmation from other sources, prove that a reaction will occur when you eat the food. In other words, the test can show a positive result or a false positive (a skin reaction even though you don’t react to the food when you eat it). False positives occur in the following scenarios:

- You have a small amount of IgE antibody to a food but are not be truly allergic to that food. You can eat the food and experience absolutely no reaction to it.

- Some proteins in foods are cross-reactive with similar proteins in other foods or even environmental allergens like pollens. This cross reactivity can lead, for example, to a falsely positive skin test for soy in a person with peanut allergy, or a positive test to wheat in a person with grass pollen allergy. See the next section, “Accounting for cross reactivity,” for details.

Remember: Take the results of skin tests with a dose of salt. Overall, up to 60 percent of all positive food skin tests turn out to be incorrect (falsely positive) upon further evaluation. Some studies show that the larger the skin test (the bigger the bump on your skin at the site of the test), the more likely a true allergy is at work, although this has not proven true in other studies. Skin test results are only one component of the diagnostic picture, allergists should evaluate them carefully and in the context of the big, clinical picture, as demonstrated in the following sidebar.

Confirming the results with other clues

Skin tests alone rarely prove much of anything. In a single week, I saw three patients, all of whom were diagnosed with egg allergy and came to me for a second opinion. Each had tested positively and had reactions of similar size to egg. Their cases illustrate the complexities of interpreting skin tests:

- Patient 1: The first patient had experienced two severe allergic reactions after eating scrambled eggs. In this case, the skin test confirmed the history and the diagnosis of egg allergy was virtually certain. This patient must avoid eating eggs.

- Patient 2: The second patient (a child) had severe eczema and was eating eggs regularly. He had never experienced an apparent reaction to egg and no evidence linked the eczema to a particular food in his diet. Since about 40 percent of children with severe eczema have underlying food allergy, and since egg allergy is the most common food allergy in children with eczema, this patient requires additional tests, as explained later in this chapter, to determine whether he is truly allergic to egg or not.

- Patient 3: The third patient was being evaluated for seasonal hay fever, and his allergist performed food tests for no particular reason. He eats eggs regularly and has never had any difficulty. Yet, his allergist told him to strictly avoid eggs, solely because he tested positive to egg. In this patient the history won. My colleagues and I felt safe assuming that the skin test produced a false positive result and that the patient could safely resume eating eggs.

Accounting for cross reactivity

Cross-reactivity can occur when your immune system confuses one protein for another one. This typically happens with members of the same food family, but can occur between two allergens you may not imagine are related. A person who’s allergic to tree pollen, for example, may not be able to eat apples or cherries. Someone who’s allergic to ragweed may be sensitive to cantaloupe or banana.

Allergists remain vigilant of cross reactivity for two reasons:

- Cross-reactivity can often provide clues to other foods you may be allergic to or may become allergic to in the future.

- Cross-reactivity can thoroughly confuse test results.

Remember: When evaluating skin tests, your doctor needs to be aware of the possibility of cross reactivity, because the test may return a false positive result for a food you can safely eat.

Weighing the minor risks of skin tests

Allergy skin testing is generally a very safe procedure. However, because it exposes you to a food that you may be highly allergic to, caution is always in order. An occasional patient may in fact be considered too allergic for administering a safe skin test. Incidence of systemic (whole body) reactions, however, are very low—estimates run at about 30 reactions per 100,000 tests.

Warning: Only allergists trained in the treatment of severe allergic reactions should perform skin tests, just in case you experience a severe reaction. Your allergist must have emergency equipment and drugs on hand for the treatment of anaphylaxis whenever performing a skin test. Chapter 2 provides more detailed information on anaphylaxis.

Hunting for IgE with RASTs

Another test that requires a needle is the RAST, a test that measures the amount of allergen-specific IgE in your blood. This test doesn’t require an allergist; your GP can perform the test, but an allergist may be more qualified to interpret the results and is usually the doctor who performs the test. RAST consists of drawing a small amount of blood and then having the blood tested—by sending it out to a lab. Doctors can perform RASTs for almost any food or airborne allergen.

RAST terminology defined

RAST (short for radioallergosorbent test) is a term that actually refers to an older test method, one that allergists rarely use any more. The term stuck, however, and doctors still commonly the term to describe all of the test methods that measure specific IgE antibodies in the blood. A more accurate term would be immunoassay for specific IgE but I use RAST throughout the book, because it’s more common and a heck of a lot easier to type.

Remember: The most important point about RASTs is that they’re not all the same. Some types of RASTs are more accurate than others, and the results of one type of RAST are not interchangeable with the results of another type. For diagnosing food allergies, the type of RAST that has the best track record is the Pharmacia CAP fluorescent enzyme immunoassay. Wrap your mouth around that one! To simplify the nomenclature, doctors refer to this type of RAST as CAP-FEIA or CAP-RAST.

As with skin testing, negative RAST results are quite accurate in ruling out an IgE-mediated food allergy, but positive RAST results do not necessarily mean you have a true food allergy. False positive results occur with RASTs for the very same reasons they occur with skin testing. However, because the RAST is more of a true measure of the amount of IgE in your system, differentiating a true positive test from a false positive test is generally easier than it is in the case of skin tests.

When your doctor gets the results, she looks at your RAST score and interprets the results based on the following criteria:

- The higher the RAST score, the more likely that the results represent a true food allergy.

- More importantly, for some of the most common food allergens, the doctor may compare your RAST levels to predetermined cut-offs, above which a true food allergy is almost certain. For example, using the CAP-RAST, which gives results on a scale from 0 (zero) to 100, an IgE level of more than 7 to egg, over 15 to milk, 14 to peanut, and 20 to codfish is highly predictive (greater than a 95 percent chance) that you’re allergic to that food.

Tip: Your doctor can often use RAST results to track your levels of specific IgE antibodies over time. RAST levels that decrease over time are an excellent indication that you’re outgrowing your allergy to a particular food. My colleagues and I typically decide when to try to re-introduce a food into a patient’s diet based on the RAST result. (See Chapter 15 for details about outgrowing food allergies.)

Weighing the pros and cons of RASTs and skin tests

As you probably realized by now, neither skin tests nor RASTs are the perfect tests. Results can range from highly successful at best, to inconclusive, to misleading at worse. When discussing with your doctor which test would be most useful in your case, weigh the pros and cons of each.

Skin tests have a couple advantages over RASTs:

- A skin test is cheap.

- Skin test results are available almost immediately.

- Skin tests generally produce fewer false negatives. However, in food allergy testing, false negatives are uncommon with either test method, so this is not a huge issue.

RASTs have several advantages over skin testing:

- Certain medications, such as antihistamines, can interfere with skin testing, so you have to stop the medication beforehand. If you have trouble stopping your antihistamines, a RAST is an attractive alternative.

- Widespread skin conditions, especially hives or severe eczema, may preclude accurate skin testing.

- RASTs are less risky for patients who are susceptible to severe anaphylaxis.

- RASTs may be better at discerning a true positive from a false positive test.

- RASTs provide more information on the progress of an allergy over time.

Remember: Neither skin-test nor RAST results are very good at predicting the type or severity of an allergic reaction. Although higher RAST levels generally indicate more severe reactions, numerous exceptions prevent RAST results from functioning as accurate predictors of a future reaction. This is due in part to the dose effect described in Chapter 3, but even with the same dose (amount of a problem food) three people with the same skin-test or RAST result may have hugely different reactions with exposure to the food. One person may eat peanuts regularly without symptoms, the second may experience minor hives, and the third may experience severe anaphylaxis.

Looking for Clues with Additional Diagnostic Tools

You’ve been interviewed, examined, and poked, and your allergist can provide you with no definitive diagnosis. It happens, especially when you’re experiencing delayed reactions. Hope, however, remains. Your doctor has some additional tricks up his sleeve, including both eating the food (a food challenge) and not eating the food (an elimination diet). The following sections present additional diagnostic tools that can dig below the skin to unearth more mysterious causes.

Daring a food to make you react: Food challenges

When your allergies prove too elusive for skin tests and RASTs, your doctor may try to dare the allergies out of hiding by challenging them to react to suspect foods. This test, commonly called an oral food challenge, consists of feeding you increasing amounts of the suspect food under your doctor’s supervision, while observing you for symptoms. Food challenges are considered the only foolproof test for most food allergies. In addition to identifying elusive allergies, food challenges serve three useful purposes:

- Verify the accuracy of a positive skin test or RAST.

- Determine if a patient has outgrown an allergy.

- Diagnose cases of non-IgE-mediated reactions. An oral challenge may be the only definitive way to diagnose a non-IgE mediated food allergy.

Warning: Don’t try this at home. Food challenges carry a risk of serious reactions. Only trained personnel with emergency treatment immediately available should perform these tests.

Your doctor can choose to perform a food challenge using either of the following three methods:

- Instruct you to eat the suspect food in increasing doses while observing you for signs of a reaction. (With this method, unlike the following two methods, you know what you’re eating.) This is the most common way to do a food challenge.

- Have you to eat something that contains the suspect food without your knowing that you’re eating the suspect food. Your doctor mixes samples of the offending food with another food or adds it as an ingredient to another food, so you can’t recognize it by sight, smell, or taste.

- Have you swallow a capsule containing the allergen. In some cases, the doctor uses placebo tablets, as well, to keep you in the dark about whether you’re eating the suspect food or some inert substance.

The ideal way to perform a food challenge test is to do a “double-blind, placebo-controlled challenge.” With this method, neither the allergist nor the patient is aware of which capsule or food contains the suspected allergen. In order for the test to be effective, you must also take capsules or eat food that does not contain the allergen (placebos). This ensures that any observed reaction is due to the allergen and not some other factor, such as stress or anxiety.

Challenging a food when the time is right

My colleagues and I often struggle to determine the right time to do a food challenge, especially to see if a patient has outgrown an allergy. If a patient has not experienced any recent reactions (recent reactions would guarantee that the patient is still allergic), we base most food challenge decisions on the CAP-RAST IgE level. If the CAP-RAST IgE level is low enough, we decide to move forward with a food challenge to verify that the patient has really outgrown the allergy.

A few years ago we published our experience with this method and were able to more clearly define the IgE levels at which a challenge may be reasonable. After all, we do not want to take the risk of a challenge if the odds of success are too small, but yet don’t want to restrict the diet more than necessary. In our study, we reported on 604 food challenges in 391 children to the five most common food allergens. Our goal was to establish the IgE level at which we could expect a 50 percent pass rate, and we determined a cutoff level of 2 kUA/L (kili-units per liter) for milk, egg, and peanut. Data were less clear for wheat and soy where determining a definitive cut-off was more difficult. We concluded that IgE concentrations to milk, egg, and peanut and, to a lesser extent, wheat and soy, serve as useful predictors of challenge outcome and should be routinely used when advising patients about oral challenges to these foods. See Chapter 15 for additional details on working with your allergist to determine when conditions are relatively safe to proceed with a food challenge to determine if you have outgrown an allergy.

Discovering your allergens by avoiding them

When you eat something and it makes you sick, the logical thing to do is stop eating it. This is essentially what you do with an elimination diet. When you have a food allergy, your doctor often places you on an elimination diet permanently, or until you’ve outgrown the allergy (if you do outgrow the allergy), but doctors often use elimination diets on a temporary basis to diagnose allergies.

You may have already performed this test on your own by avoiding a particular food and then re-introducing it to your diet and finding that your symptoms returned. If you’ve already done this, your doctor should have included this piece of information in your history. If you haven’t performed the test yet, your doctor may recommend it to confirm skin test or RAST results or simply as a logical next step–”we can’t figure this out so let’s avoid certain foods and see what happens.”

An elimination diet typically spans the course of several weeks but consists of only two steps (plus a step that’s sometimes recommended):

- Eliminate specific foods and ingredients from your diet, typically over a period of two to three weeks. During this time, you carefully read food labels and find out about food preparation methods when you’re dining out. See Chapter 6 for details about reading labels. Over the course of the elimination period, your doctor monitors symptoms, all of which should disappear in three weeks if you’re following the right diet.

- With your doctor’s okay, you begin to gradually reintroduce the foods that were eliminated, one at a time, while carefully recording any symptoms that arise when you partake of each food. If your symptoms return, your doctor can usually confirm the diagnosis.

- In some cases, your doctor may direct you to once again eliminate the remaining suspect foods from your diet to reinforce the diagnosis.

Maybe you’re thinking that elimination diet is just a fancy term for food challenge, and it sort of is. You eliminate the food and then challenge it.

Remember: The elimination diet is not foolproof, and it can be risky. Psychological and physical factors can affect the diet’s results. For example, if you think you’re sensitive to a food, a response could occur that may not be a true allergic one. And if you’ve experienced severe reactions to certain foods, your doctor should consider reintroducing the food only in the controlled setting of a food challenge.

Cracking a tough case

Some patients have extremely challenging food allergies that defy the detection efforts of even the most determined and well-trained allergist. To demonstrate just how challenging the diagnostic process can be, I offer a case that typifies the usual patient that I see in my food allergy clinic on a daily basis:

Kyle is a two-and-a-half-year-old old boy who had severe eczema in the first weeks of life. His mother was breast-feeding him at that time, and he seemed to react to whatever his mother was eating. He underwent his first allergy testing at six months of age, and the results showed positive to milk, egg, and peanut. He was weaned to a soy formula, which he appeared to tolerate. By the time he saw me for the first time, he had been skin tested three more times, each test picking up more positive results. A detailed diet history revealed that his only obvious allergic reactions occurred with exposure to egg and milk. He had never ingested peanut or tree nuts and had seemed to tolerate wheat and soy.

Kyle’s previous doctors told his parents that he was truly allergic to all of the foods to which he tested positive. By the time I saw him, his diet was limited to seven foods—rice, apple, pear, chicken, squash, sweet potato, and carrots. Although his eczema was now well under control, he was losing weight and was miserable. The elimination diet had worked to improve his eczema and had been helpful, diagnostically speaking, by showing that his eczema was due to food allergy, but it had truly put him at risk of malnutrition. Given the likelihood that many of his skin test results were falsely positive, I was hopeful that we could expand his diet.

I began by performing RASTs to a large panel of foods. With these results we could put the foods he was avoiding into three categories—almost definitely allergic, possibly allergic, and almost certainly not allergic. I felt that the foods in the last category—almost certainly not allergic—could be safely introduced at home. We were able to quickly expand his diet to include several major foods, including wheat, soy, and corn, as well as many new fruits and vegetables, with no worsening of his eczema. For the foods in the middle category—possibly allergic—I recommended that food challenges be done to further define his true allergies. This allowed us to introduce pork, oat, and potato into his diet. Food challenges to milk and beef were unsuccessful. For the foods in the first category—almost definitely allergic—including egg, peanut, tree nuts, sesame, peas, and fish, I recommended continued strict avoidance.

At this point, while his diet is still very restricted, his life and nutrition are both vastly improved. He will now be retested annually and his diet hopefully will expand further with time.

Pursuing the causes of non-IgE mediated allergies

As described in Chapter 1 and elsewhere, some types of allergy involve other parts of the immune system and are undetectable with the most common allergy tests—skin tests and RASTs. These are mostly gastrointestinal reactions, although occasionally eczema and other rashes may occur due to non-IgE mediated food allergies.

In such cases, allergists typically have to fall back on your history, which may range from tremendously helpful to completely misleading, especially if you experience delayed reactions or you and your doctor can’t pin down a specific food. If the history reveals little useful information, your doctor may recommend one of the following next steps:

- The first next step is usually an elimination diet followed by either an oral food challenge or a gradual re-introduction of the food(s) at home.

- The second diagnostic approach is to perform a biopsy of the esophagus, stomach, or intestine (obtained through a scope by a gastroenterologist). To obtain the most definitive results, your allergist (with the assistance of your gastroenterologist) may repeat the scope and biopsies after an elimination diet or after you’ve re-introduced the food into your diet.

Another type of skin testing called patch testing has shown some promise in the diagnosis of non-IgE mediated food allergy. When used for food reactions, small amounts of a pure food are placed in tiny cups, which your doctor tapes to your back. The foods are chosen based on diet, knowledge of common allergens, and previous reactions. Your doctor removes the patches after 48 hours and reads them at 72 hours. During the writing of this book, no standardized reagents, application methods, or guidelines for interpretation are available, and patch testing is still finding its place in the diagnosis of food allergy.

Avoiding the untested and unproven

Admittedly, skin tests and RASTs, are less than perfect, but some allergy tests, often purported to be superior, are untested at best, proven to be worthless at their worst, and are usually pretty costly (and not covered by insurance). I commonly see patients who have spent thousands of dollars of these tests and who have been placed on broad avoidance diets based on totally inaccurate test results. Remember those quackologists I talked about earlier in this chapter. They’re typically the misinformed, misguided souls who mislead their patients with these phony tests. Here’s a list of the most common dubious tests to watch out for:

- IgG and IgG4 tests

- Sublingual or intradermal provocation tests

- Lymphocyte activation tests

- Kinesiology

- Cytotoxic tests

- Electrodermal testing

For details about unproven tests and treatments you need to watch out for, skip to Chapter 8.

Ruling out food intolerances

Certain foods can make you miserable even though you’re not allergic to them. If your doctor examines your body, your history, and your test results and rules out food allergy, he may begin to suspect a food intolerance—an adverse food-induced reaction that does not involve the immune system.

Lactose intolerance is one example of a food intolerance. If you have a lactose intolerance, you lack an enzyme (lactase) that’s essential for digesting milk sugar. In this case, the milk sugar is the culprit. In the case of a milk allergy, a milk protein is the perpetrator. When a person with lactose intolerance consumes milk products, symptoms such as gas, bloating, and abdominal pain may occur. Your doctor can perform a specific test for lactose intolerance called a breath hydrogen test, but for most other food intolerances no specific diagnostic test is available.

To diagnose an intolerance to other foods, such as wheat, your doctor is likely to re-examine the data he’s already collected:

- History: A history that shows a predominance of gastrointestinal symptoms and a tolerance of small doses of the food commonly points to food intolerance. With food intolerance, symptoms typically occur when you eat larger quantities of the suspect food. While this can occur with food allergy, allergic reactions tend to occur at much smaller doses than food intolerances.

- Test results: If your skin tests and RASTs show no signs of food allergy, a food intolerance may be triggering your symptoms.

Treatment for a food intolerance is very similar to food allergy treatment. Your doctor is likely to instruct you to avoid the offending foods or at least limit your consumption. The same food substitutes can often help you vary your diet without missing the foods you love. In the case of lactose intolerance, your doctor may prescribe lactase supplements to help you digest the milk sugar.